How to Bring Something to the Table Without Cooking this Thanksgiving

Directions: Have your family members and friends fill in the blanks for “A Moveable Fast” written by Elyssa East as an Op-ed article for the New York Times in November of 2009 and created as a Thanksgiving Fill-In by Katherine Schulten.

Use your own words, or peek, if you must, from the list of the words below the article.

“It’s Thanksgiving — time to put our _________ on,” my family likes to say as we _________ for room next to the Pilgrim and _________ ghosts the holiday summons to our table. Our colonial _________ probably would not disapprove of our having second and third helpings of sweet potatoes and stuffing, or even rushing off to watch _________ after the meal — the Pilgrims themselves played lots of games at that first Thanksgiving in 1621. But I _________ they would find fault with our _________ for another reason: it is not accompanied by a _________.

To the Pilgrims and Puritans, the community-wide fast, or “day of public humiliation and prayer,” and the thanksgiving feast, or day of “public thanksgiving and praise,” were equal _________ of the same _________. But the fast was not merely a _________ for a community-wide gorging. Both customs were important components of a religious rite that served to _________ an _________ God who was believed to punish entire communities for the sins of the few with starvation, “excessive rains from the bottles of heaven,” _________, crop infestations, the Indian wars and other hardships.

According to the 19th-century historian William DeLoss Love, the New England colonies _________ as many as nine such “special public days” a year from 1620 to 1700. And as the Puritans were masters of _________, days of abstention outnumbered thanksgivings two to one. Fasting, Cotton Mather wrote, “kept the wheel of prayer in continual motion.”

_________ for rain during spells of drought were the most common reason for fasting. But Puritans also fasted whenever a _________, an evil portent, appeared in the sky; at the start of the Salem witch trials; and throughout the various colonial Indian wars (Mather _________ that the horrors in King Philip’s War, against the Wampanoag Indians, had been sent by God to chastise colonists for the sin of _________).

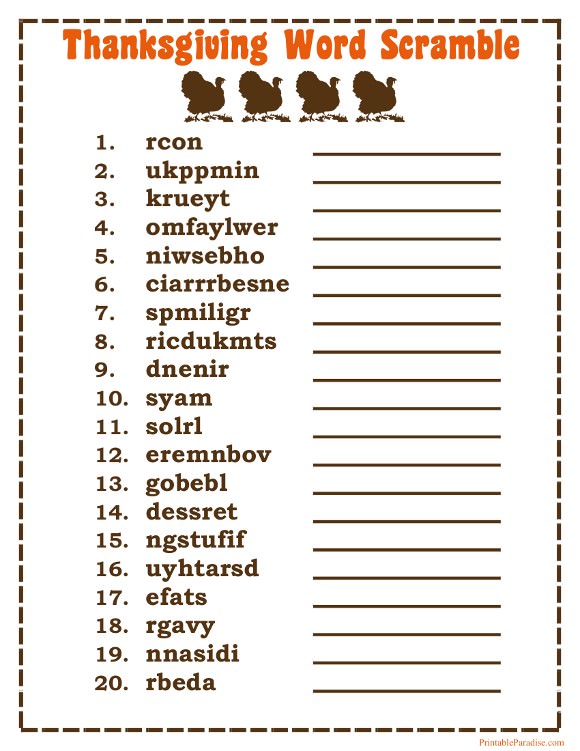

Word List

- wig wearing

- fast

- Puritan

- forebears

- equal

- binge

- pleas

- imagine

- self-denial

- elbow

- ritual

- epidemics

- pacify

- preached

- justification

- comet

- celebrated

- football

- angry

- feed bags

Educate your Families and Friends with this Fascinating Op-ed

A Moveable Fast

By Elyssa East November 23, 2009

“IT’S Thanksgiving — time to put our feedbags on,” my family likes to say as we elbow for room next to the Pilgrim and Puritan ghosts the holiday summons to our table. Our colonial forebears probably would not disapprove of our having second and third helpings of sweet potatoes and stuffing, or even rushing off to watch football after the meal — the Pilgrims themselves played lots of games at that first Thanksgiving in 1621. But I imagine they would find fault with our binge for another reason: it is not accompanied by a fast.

To the Pilgrims and Puritans, the community-wide fast, or “day of public humiliation and prayer,” and the thanksgiving feast, or day of “public thanksgiving and praise,” were equal halves of the same ritual. But the fast was not merely a justification for a community-wide gorging. Both customs were important components of a religious rite that served to pacify an angry God who was believed to punish entire communities for the sins of the few with starvation, “excessive rains from the bottles of heaven,” epidemics, crop infestations, the Indian wars and other hardships.

According to the 19th-century historian William DeLoss Love, the New England colonies celebrated as many as nine such “special public days” a year from 1620 to 1700. And as the Puritans were masters of self-denial, days of abstention outnumbered thanksgivings two to one. Fasting, Cotton Mather wrote, “kept the wheel of prayer in continual motion.”

Pleas for rain during spells of drought were the most common reason for fasting. But Puritans also fasted whenever a comet, an evil portent, appeared in the sky; at the start of the Salem witch trials; and throughout the various colonial Indian wars (Mather preached that the horrors in King Philip’s War, against the Wampanoag Indians, had been sent by God to chastise colonists for the sin of wig wearing).

Thanksgivings were celebrated at the end of these and other hardships and in honor of such auspicious events as the “dissipation of the pirates,” the succession of English kings and safe ocean crossings of ships bearing colonists and much needed supplies. Yet these feasts all began with fasts and hours of prayer, during which ministers praised God’s goodness and railed against the sin of gluttony. (Once, after eating too much, John Winthrop, the governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony, fretted that his flesh had “waxed wanton” and begged God to “revive” him.) Intemperance was believed to go against the very idea of gratitude. Of course, people did often overindulge at these thanksgivings. But then additional fast days often immediately followed.

Puritans believed that expressions of thanks to God for their good fortune helped keep his future punishments at bay — a point that does not detract from the genuine appreciation they felt at privations’ end. Nonetheless, participation was mandatory. In 1696, William Veazie of Boston was pilloried for plowing on Thanksgiving Day.

It was in the late 1660s that the New England colonies began holding an “Annual Provincial Thanksgiving.” The holiday we celebrate today is a remnant of this harvest feast, which was theologically counterbalanced by an annual spring fast around the time of planting to ask God’s good favor for the year. Yet fasting and praying also immediately preceded the harvest Thanksgiving. In 1690, in Massachusetts the feast itself was postponed, though not the fasting, out of extraordinary concern that the meal would inspire too much “carnal confidence.”

As life in the New World wilderness got easier, the New England colonies gradually began holding only their annual spring fast and fall harvest feast. Even after Abraham Lincoln established Thanksgiving as a national holiday in 1863, Massachusetts continued to celebrate its spring day of abstention for 31 more years.

In the nearly 400 years since the first Thanksgiving, the holiday has come to mirror our transformation into a nation of gross overconsumption, but the New England colonists never intended for Thanksgiving to be a day of gluttony. They dished up restraint along with gratitude as a shared main course. What mattered most was not the feast itself, but the gathering

together in thanks and praise for life’s most humble gifts. Perhaps this holiday season we could benefit from restoring a proper Thanksgiving balance between forbearance and indulgence.

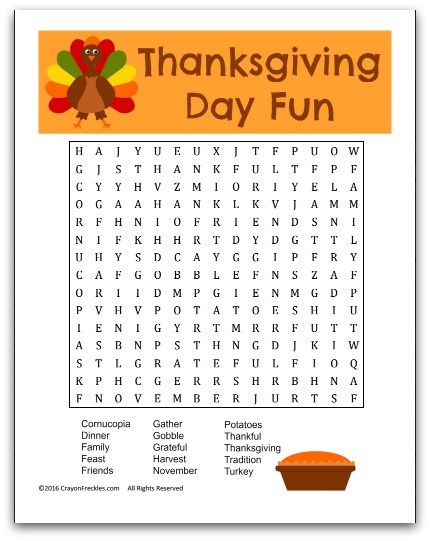

After Dinner Fun

Refer to the following links for more information.

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/24/opinion/24east.html#story-continues-2

https://learning.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/11/24/thanksgiving-fill-in/

http://www.printableparadise.com/printable-word-scrambles.html

http://www.crayonfreckles.com/

For more articles by Virginia Tortorici, click here.